Dies ist der gesamte Blog unserer Rundreise durch das südliche Südamerika

Es ist die Rundreise vom südamerikanischen Winter (Anfang August) bis in den darauf folgenden Herbst (Anfang Mai) durch Uruguay, Argentinien, Chile und zurück (auf 10 langen Seiten), einschließlich der Zusammenfassung:

This is the entire blog of our round trip through southern South America Zum Auftakt unserer großen Reise durch die südlichen Länder Südamerikas sind wir in Montevideo angekommen, der Hauptstadt von Uruguay. Das Schiff, auf dem unser Wohnmobil hierher transportiert wurde, war gut im Fahrplan, bis es Brasilien erreichte. Ab dort hat es sich in jedem angelaufenen Hafen (weiter) verspätet. Mit fast drei Tagen Verspätung hat es hier den Hafen erreicht und wir hoffen, in den nächsten Tagen das Womo abholen zu können. Ohnehin haben wir hier erst mal für ein paar Tage ein Hotelzimmer, um uns nach dem langen Flug und wegen der fünfstündigen Zeitverschiebung zu akklimatisieren. Für einen Tag haben wir zunächst den Hotelaufenthalt verlängert. Bei extremen Sommertemperaturen sind wir aus Europa abgeflogen: Hamburg 31°C, Zwischenlandung in Madrid 39°C. Auf der Südhalbkugel ist Winter, Montevideo ist die südlichste Hauptstadt Südamerikas. Etwa 10° bis 12°C sind hier Anfang August offenbar die üblichen Tagestemperaturen, allerdings oft mit kräftigem, kaltem Wind; die Altstadt ist an drei Seiten von Wasser umgeben. Dazu scheint häufig die Sonne und wir können bei Spaziergängen die Stadt erkunden. Viele Gebäude, Straßen und Plätze der Altstadt lassen früheren Wohlstand erkennen. Vieles ist renovierungsbedürftig. Aber bei aufmerksamem Beobachten entdecken wir immer wieder gut erhaltene Häuserfronten. Wandmalereien sind weit verbreitet, viele sehr gut gemacht, häufig mit politischen Parolen. Selbstverständlich gibt es auch moderne Glaspaläste.

At the start of our great journey through the southern countries of South America, we arrived in Montevideo, the capital of Uruguay. The ship that transported our motorhome here was well on schedule until it reached Brazil. From there on, it was (further) delayed in every port of call. It reached the port here almost three days late and we hope to be able to pick up the motorhome in the next few days. Anyway, we have a hotel room here for a few days to acclimatise after the long flight and because of the five-hour time shift. For one day first, we extended our stay in the hotel. We flew out of Europe in extreme summer temperatures: Hamburg 31°C, stopover in Madrid 39°C. It is winter in the southern hemisphere, Montevideo is the southernmost capital of South America. About 10° to 12°C are apparently the usual daytime temperatures here at the beginning of August, but often with a strong, cold wind; the old town is surrounded by water on three sides. In addition, the sun often shines and we can explore the city on walks. Many buildings, streets and squares in the old town show signs of former prosperity. Much is in need of renovation. But with attentive observation, we discover well-preserved house fronts again and again. Murals are widespread, many very well done, often with political slogans. Of course, there are also modern glass palaces.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Ein wesentliches Element der Stadt Montevideo ist die 22 km lange Rambla, die Promenade am Rio de la Plata. Dort ist eine Tafel angebracht, die den Fundort eines kleinen Sauriers markiert. Unterbrochen wird die Rambla im Westen der Altstadt vom Hafen. Hier staunen wir, wie nahe wir auf dem Fußweg den Straddle Carriern kommen, die dort (hinter dem Hafenzaun) die Container transportieren.

An essential element of the city of Montevideo is the 22 km long Rambla, the promenade along the Rio de la Plata. There is a plaque there marking the site where a small dinosaur was found. The Rambla is interrupted in the west of the old town by the port. Here we are amazed at how close we come to the straddle carriers on the footpath, which transport the containers there (behind the port fence).

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mit nur einem Tag Verspätung haben wir unser Wohnmobil aus dem Hafen heraus bekommen. Dafür waren einige bürokratische Vorgänge erforderlich, die wir gleich am Tag unserer Ankunft in Montevideo erledigt haben: Bei der Einwanderungsbehörde(!) haben wir in der lange Schlange bis auf die Straße angestanden und ein „Zertifikat der Ankunft“ beantragt und bekommen. Das haben wir beim Zollagenten abgegeben. Der hat die Dokumente vom Fahrzeug und vom Halter kopiert und mit den Daten daraus einen Antrag an den Zoll gefertigt. Bei der Agentur der Reederei waren einige hundert US-Dollar zu bezahlen, dafür hat sie das Bill of Lading erstellt und dem Zollagenten übergeben. Als das Wohnmobil vom Schiff abgeladen war, hat der Zollagent mit den gesammelten Dokumenten die Freigabe des Fahrzeugs per E-Mail beantragt. Am selben Tag war sie abends erteilt. Die Erleichterung war groß, als zu sehen war, dass das Womo unversehrt ist. Alle Türen und die großen Ausstellfenster waren mit Siegeln beklebt, die den Schriftzug „void“ (ungültig) hinterlassen, wenn sie gebrochen werden. Der Zoll hat innen alle Fächer geöffnet (die hatten wir, wie von Seabridge empfohlen, mit Klebestreifen fixiert, damit sich auf See nichts öffnet). In den Fächern war aber nichts durcheinander gebracht. Hundepfoten-Spuren im Womo lassen auf einen Drogenspürhund schließen. Der Herumkommer hat dann zunächst Frau Rumkommer mit dem Fluggepäck aus der Hotel-Lobby geholt. Dann haben wir Frischwasser und Diesel getankt und die beiden Propangasflaschen füllen lassen. Danach war bis Einbruch der Dunkelheit gerade noch Einkaufen der nötigsten Lebensmittel möglich. Einen guten Stellplatz haben wir dann am Rand von Montevideo gefunden. Nach Süden hin erstreckt sich von der Stadt eine Landzunge. An deren Ende steht der Leuchtturm Faro de Punta Carretas, umgeben von Felsen im Wasser. Direkt daneben ist eine Kläranlage, die „stört“. Aber ein paar hundert Meter nördlich sind viele gute Stellplätze, die augenscheinlich gern genommen werden.

At the Rio de la Plata We got our motorhome out of the port with only one day’s delay. This required some bureaucratic procedures, which we took care of right on the day of our arrival in Montevideo: At the immigration office(!) we waited in the long queue all the way to the street and applied for and received a „certificate of arrival“. We handed it in to the customs agent. He copied the documents of the vehicle and the owner and prepared an application to customs with the data from them. We had to pay a few hundred US dollars to the shipping company’s agency, for which they prepared the Bill of Lading and handed it over to the customs agent. When the motorhome was unloaded from the ship, the customs agent used the collected documents to apply for the vehicle’s release by email. It was granted in the evening of the same day. The relief was great when it was seen that the camper van was intact. All the doors and the large hinged windows had seals stuck on them, which leave the words „void“ if they are broken. Customs opened all the compartments inside (as recommended by Seabridge, we had fixed them with adhesive tape so that nothing would open at sea). But nothing was mixed up in the compartments. Dog paw marks in the camper suggest a drug-sniffing dog. The Aroundgetter then first fetched Mrs Roundgetter with the flight luggage from the hotel lobby. Then we filled up with fresh water and diesel and had the two propane bottles filled. After that, it was just possible to go shopping for the most necessary groceries until nightfall. We found a good pitch on the outskirts of Montevideo. To the south, a spit of land extends from the city. At its end is the Faro de Punta Carretas lighthouse, surrounded by rocks in the water. Right next to it is a sewage treatment plant that „disturbs“. But a few hundred metres to the north there are many good pitches that are apparently very popular.

. . . . . . . Beim Blick auf den Rio de la Plata fällt es schwer zu glauben, dass es kein Meer sondern eine sehr breite Flussmündung ist. Kilometerlange Sandstrände gibt es hier, gelegentlich unterbrochen von Felsen. In Atlántida, einige Kilometer östlich von Montevideo, haben wir wieder eine große Auswahl an Stellplätzen, hier oberhalb des Strandes. Mitte August (entspricht Mitte Februar auf der Nordhalbkugel) blühen hier schon einige Sträucher. Gebadet wird hier jetzt selbstverständlich nicht, aber unzählige Angler sind am Strand aufgereiht. Am Abend erfreut uns sogar noch ein Vollmond über dem Wasser.

Looking at the Rio de la Plata, it is hard to believe that it is not a sea but a very wide estuary. There are kilometres of sandy beaches here, occasionally interrupted by rocks. In Atlántida, a few kilometres east of Montevideo, we again have a wide choice of pitches, here above the beach. In mid-August (equivalent to mid-February in the northern hemisphere), some shrubs are already in bloom here. Of course, there is no swimming here now, but countless anglers are lined up on the beach. In the evening, we even enjoy a full moon over the water.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Das östliche Ende des Rio de la Plata ist Punta del Este. Es heißt, dass kein anderer Ort Lateinamerikas so sehr vibriert. Von der kleinen Landzunge Punta del Chileno, im Westen von Maldonado (das übergangslos in Punta übergeht), haben wir nicht nur einen großartigen Blick auf die Skyline der Bettenburgen sondern auch einen herrlichen Übernachtungsplatz.

The eastern end of the Rio de la Plata is Punta del Este. It is said that no other place in Latin America vibrates as much. From the small headland of Punta del Chileno, to the west of Maldonado (which merges seamlessly into Punta), we not only have a great view of the skyline of the bed castles but also a wonderful pitch for the night.

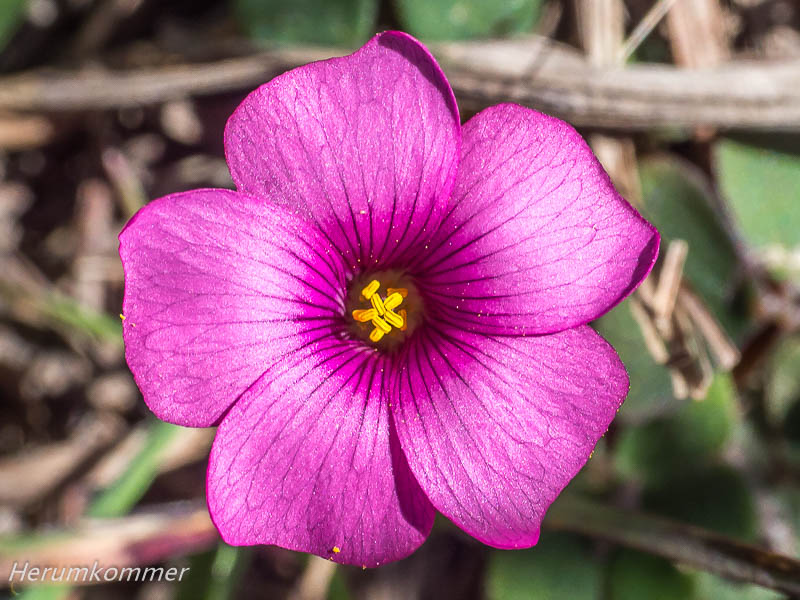

. . . Als wir der Stadt näher kommen, können wir erkennen, dass auf ihrem südlichen Zipfel, um den Leuchtturm herum, keine Hochhäuser stehen. Sie würden das Licht vom Turm abschatten. Hier ist es kleinstädtisch beschaulich im uruguayischen Winter (aber nicht winterlich bei 21°C). Auf akkurat gepflegten Rasenflächen an Bürgersteigen leuchten uns hellblaue Blumen entgegen. Der Leuchtturm steht in einem begrünten Straßenrechteck. Gegenüber, im kleinen Turm, ist die Wetterstation. Und hier parkt einer der sehr alten Oldtimer, für die Uruguay bekannt ist: ein Ford, zugelassen in der Stadt Mercedes.

As we get closer to the city, we can see that there are no high-rise buildings on its southern tip, around the lighthouse. They would shade the light from the tower. Here it is small-town tranquil in the Uruguayan winter (but not wintry at 21°C). On meticulously manicured lawns along pavements, bright blue flowers shine out at us. The lighthouse stands in a leafy street rectangle. Opposite, in the small tower, is the weather station. And here is parked one of the very old classic cars for which Uruguay is famous: a Ford, registered in the city of Mercedes.

. . . . . . . . . . . Am äustersten Ende von Punta del Este, Punta de las Salinas, klärt uns eine Tafel auf, dass dies der südlichste Punkt Uruguays ist. Ab hier nach Nordosten ist das Wasser (des Atlantik) rauer, als das nach Westen (Rio de la Plata). Anders als Montevideo ist Punta del Este sehr ordentlich, die Straßen sind in gutem Zustand, die Gebäude sowieso. Ein weiteres Wahrzeichen der Stadt ist La Mano (Die Hand) des chilenischen Künstlers Mario Irrazábal; inzwischen ist es als Los dedos (Die Finger) bekannt.

At the extreme end of Punta del Este, Punta de las Salinas, a sign tells us that this is the southernmost point of Uruguay. From here to the northeast, the water (of the Atlantic Ocean) is rougher than that to the west (Rio de la Plata). Unlike Montevideo, Punta del Este is very tidy, the streets are in good condition, the buildings anyway. Another landmark of the city is La Mano (The Hand) by the Chilean artist Mario Irrazábal; it is now known as Los dedos (The Fingers).

. . . . . . . . . Unterhalb des Leuchtturms Faro de José Ignacio bietet sich uns ein Bild, ähnlich wie es uns aus Skandinavien vertraut ist: Schärenküste wie bei Göteborg.

Skerries at Uruguay’s coast Below the Faro de José Ignacio lighthouse we see a picture similar to the one we are familiar with from Scandinavia: a skerry coast like near Gothenburg.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Stellenweise liegt Sandstrand zwischen den Felsen. Hier sind sie an Land gespült: Unzählige eiförmige, Hühnerei-große, gelbliche „Blasen“. Einige sind geschlossen und voll Wasser. Die meisten sind (vermutlich von der Wucht der Wellen) aufgebrochen und mehr oder weniger leer; die leeren verschrumpeln an der Luft. Die Hülle, etwa einen halben Millimeter dick, erscheint ähnlich wie Gelatine, ist aber offenkundig nicht wasserlöslich. Wir haben keine Ahnung, was das ist, aber es fasziniert uns.

In places there is sandy beach between the rocks. Here they have washed ashore: countless egg-shaped, chicken-egg-sized, yellowish „bubbles“. Some are closed and full of water. Most are broken open (presumably by the force of the waves) and more or less empty; the empty ones shrivel up in the air. The shell, about half a millimetre thick, appears similar to gelatine, but is obviously not water soluble. We have no idea what it is, but it fascinates us.

. . . . . . . . . . .

Am Rand von La Paloma, unweit des Leuchtturms Faro de Cabo de Santa Maria, haben wir einen schönen Stellplatz gefunden, am Strand, fünfzig Meter vom Meer entfernt. Direkt vor uns zieht sich Flysch ins Meer. Über hunderte Meter entlang des Strandes unterhalb des Leuchtturms gibt es eine große Vielzahl von Varianten.

Flysch at La Paloma At the edge of La Paloma, not far from the lighthouse Faro de Cabo de Santa Maria, we found a nice pitch, on the beach, fifty metres from the sea. Directly in front of us, Flysch stretches into the sea. For hundreds of metres along the beach below the lighthouse, there is a great variety.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Einige Kilometer nördlich von La Paloma, noch jenseits von La Pedrera, haben wir einen Feldweg in ein Dünengebiet gefunden. Sehr weit verstreut stehen hier in San Antonio einzelne Sommerhäuser, die solche Wege als Zufahrten haben. Hier genießen wir zunächst die Dünenlandschaft. Dann machen wir einen Spaziergang zum Atlantik, der hier wild auf den Sandstrand brandet.

San Antonio Beach A few kilometres north of La Paloma, still beyond La Pedrera, we found a dirt road into a dune area. Very widely scattered here in San Antonio are individual summer houses that have such paths as access roads. Here we first enjoy the dune landscape. Then we take a walk to the Atlantic Ocean, which crashes wildly onto the sandy beach.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Der östlichste Ort an der uruguayischen Küste ist Chuy, eine Doppelstadt, denn die Grenze zu Brasilien läuft mitten hindurch. Die brasilianische Seite heißt Chuí. So weit so gut. Aber die Grenze verläuft zwischen zwei parallelen Straßen, die über einige hundert Meter quasi eine ist, von der je eine Fahrtrichtung in Uruguay und in Brasilien verläuft. Sobald die uruguayische Straße Gegenverkehr zulässt, sind wir wieder aus Brasilien zurück, denn an Grenzformalitäten sind wir hier und jetzt nicht interessiert, wir wollen nur weiter nach Norden. Die Region westlich und nördlich von Chuy ist sehr flaches Land. Hier sind weite Landstriche als Sumpfland in den Karten verzeichnet. Nordwestlich fahren wir viele Kilometer durch durch Weideland, das immer wieder großflächig von Sümpfen, Wasserläufen und Seen unterbrochen ist. Charakteristisch zeigt sich dieses Bild bei der Brücke über den Wasserlauf, der Isla Negra benannt ist.

The easternmost town on the Uruguayan coast is Chuy, a double town, because the border with Brazil runs right through it. The Brazilian side is called Chuí. So far so good. But the border runs between two parallel roads, which for a few hundred metres is more or less one, with one direction of travel in Uruguay and the other in Brazil. As soon as the Uruguayan road allows oncoming traffic, we are back out of Brazil, because we are not interested in border formalities here and now, we just want to continue north. The region west and north of Chuy is very flat land. Here, large stretches of land are marked as swamps on the maps. To the northwest, we drive for many kilometres through pastureland that is repeatedly interrupted by large areas of swamps, watercourses and lakes. This picture becomes characteristic at the bridge over the watercourse named Isla Negra.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Von einer Raben-Kolonie, die hier lebt, hat der Nationalpark nordwestlich von Treinta y Tres seinen Namen: Schlucht der Raben. Es ist eine riesige Felsspalte. Ein etwa 3 km langer Rundwanderweg führt durch Dschungel über Stock und Stein. Zunächst geht es noch recht beschaulich bergab, dann über Felsbrocken steil bergan. Entlang einem Höhenrücken führt ein fast normaler Pfad, dann steil abwärts über Felsen. Ohne kurze Treppen und Seilführungen wäre es kaum möglich, hier bis zum Grund der Schlucht und über Felsspitzen wieder hinauf zu gelangen. Die letzten 500 m sind behindertengerecht ausgebaut, sodass man ohne Schwierigkeiten vom Parkplatz bis zu der Aussichtsplattform kommen kann, an der der schweißtreibende Aufstieg endet.

The national park northwest of Treinta y Tres takes its name from a colony of ravens that lives here: Ravens‘ Ravine. It is a huge crevice in the rock. A circular trail about 3 km long leads through jungle over hill and dale. At first, the path goes downhill quite peacefully, then steeply uphill over boulders. Along a ridge, an almost normal path leads, then steeply downhill over rocks. Without short stairs and rope guides, it would hardly be possible to get to the bottom of the gorge here and back up over rocky peaks. The last 500 m are handicapped-accessible, so that you can easily get from the car park to the viewing platform where the sweaty climb ends.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Die Verlängerung der argentinischen Pampa ist in Uruguay der Campo. Fast endlose Weiden, ordentlich eingezäunt, damit keines der unzähligen Rinder, der vielen Schafe oder der zahlreichen Pferde verloren geht. Das Land ist flach, stellenweise hügelig. Unterbrochen wird das Weideland gelegentlich durch eine Baumgruppe, ein Wäldchen oder eine Baumplantage, meistens Eukalyptus mit ihren charakteristischen Erscheinungsbildern. Immer wieder mal treffen wir einen Gaucho auf seinem Pferd, oder zwei, stets mit Hunden. Und dann haben wir das Glück, einen Baum zu sehen, der gar kein Baum ist sondern zu den Gräsern gehört: Der Ombu mit seinen gewaltigen Wurzeln.

The extension of the Argentinean pampas in Uruguay is the campo. Almost endless pastures, neatly fenced so that none of the countless cattle, the many sheep or the numerous horses get lost. The land is flat, hilly in places. The pastureland is occasionally interrupted by a group of trees, a grove or a tree plantation, mostly eucalyptus with their characteristic appearance. Every now and then we meet a gaucho on his horse, or two, always with dogs. And then we are lucky enough to see a tree that is not a tree at all but belongs to the grasses: the ombu with its enormous roots.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . In dem riesigen, fast menschenleeren Campo mit den zahllosen Nutztieren sind uns auch ein paar wilde Tiere begegnet, die dort offenbar ganz gute Lebensbedingungen haben: Wasservögel, fast so groß wie Schwäne, aber mit kleinen Schnäbeln; Vögel, die auf Strommasten, Schilderständern und anderen Pfählen sowie in Bäumen umgekehrte Schwalbennester mit verschränktem Eingang bauen; Nandús, die südamerikanischen Strauße (die Travestieshow ihrer Verwandten in Namibia war besser!); Störche mit fast weißem Schnabel, ein kleiner Hirsch. Blattschneider-Ameisen hatten wir weiter nördlich in Brasilien vermutet. Die grünen Wellensittiche in kleinen Schwärmen und die vielen Greifvögel, die wir gesehen haben, waren immer zu schnell verschwunden.

Wildlife in the Campo In the huge, almost deserted Campo with its countless farm animals, we also encountered a few wild animals that apparently have quite good living conditions there: Waterfowl, almost as big as swans, but with small beaks; birds that build inverted swallows‘ nests with folded entrances on electricity poles, sign posts and other poles as well as in trees; Nandús, the South American ostriches (the travesty show of their relatives in Namibia was better!); storks with almost white beaks, a small deer. Leafcutter ants we had suspected further north in Brazil. The green budgies in small flocks and the many birds of prey we saw were always gone too quickly.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Bevor wir von Uruguay nach Argentinien weiter reisen, haben wir am Salto Grande, einen besonders schönen Stellplatz am Wasser. Der See ist ein Gemeinschaftsprojekt beider Staaten, der den Grenzfluss Rio Uruguay auf einer riesigen Fläche aufstaut. Allein für Uruguay deckt das Kraftwerk ungefähr 2/3 des gesamten Strombedarfs. Hier am Stausee können wir besonders gut beobachten, was wir schon in den vergangenen Tagen unterwegs wahrgenommen haben: Der Frühling bricht sich Bahn, im letzten Drittel des August. Sogar Kameldornbäume blühen hier und verströmen ihren süßen Duft. Und am Abend bekommen wir noch ein Highlight im Wortsinn: ein traumhafter Sonnenuntergang.

At the Salto Grande Before we travel on from Uruguay to Argentina, we have a particularly beautiful pitch at the water at the Salto Grande. The lake is a joint project of both countries that dams up the border river Rio Uruguay over a huge area. For Uruguay alone, the power station covers about 2/3 of the total electricity demand. Here at the reservoir we can observe particularly well what we have already noticed in the past days on the road: Spring is making its appearance, in the last third of August. Even camel thorn trees blossom here and exude their sweet fragrance. And in the evening we get a highlight in the literal sense of the word: a dreamlike sunset.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Nach zweieinhalb Wochen in Uruguay, davon dreizehn Tage und etwa 1.400 km im Wohnmobil, verlassen wir das Land vorerst. Im April, im südamerikanischen Herbst, wollen wir zurück sein. Auf dem Staudamm des Embalse Salto Grande überqueren wir die Grenze zu Argentinien. Die Pass- und Zoll-Abfertigung beider Länder ist in einem Gebäude auf argentinischer Seite. Hier ist höchste Konzentration gefragt. Es dauert eine Weile, bis wir beim uruguayischen Zoll die zuständige Person finden, die uns den vom Zoll in Montevideo ausgestellten „Pass“ für das Fahrzeug abnimmt und den Vorgang digital abschließt. Ausreisestempel in unsere Pässe gibt es nicht, die sind abgeschafft. Bei der argentinischen Einreisebehörde werden unsere Daten digital erfasst, hier gibt es nicht mal einen Einreisestempel. Alle Ein- und Ausreisen werden digital erfasst und bearbeitet, an allen Grenzübergängen. Wir müssen hoffen, dass das auch überall so funktioniert. Der junge Mann, der uns hier „bearbeitet“ hat, spricht gut englisch und begleitet uns zum argentinischen Zoll. Dort motiviert er den älteren Zöllner, der offenkundig mit der Datenverarbeitung hadert, die Daten unseres Wohnmobils samt Fahrer aufzunehmen. Es dauert ein wenig, bis der uns das Dokument ausgestellt hat, dessen uruguayisches Pendant wir vorher abgeben mussten. Nach rund einer Stunde können wir in Argentinien einreisen (und 90 Tage bleiben). Als Erstes müssen wir einige Besorgungen erledigen. Auf dem Weg nach Concordia tanken wir, der Kraftstoff ist hier billiger als in Uruguay. Dann beschaffen wir eine SIM-Karte für das mobile Internet. Bei Claro, dem Netzprovider mit der besten Netzabdeckung in Argentinien, bekommen wir die Karte kostenlos. Um sie nutzen zu können, muss sie aufgeladen werden. Das geht im großen Geschäft von Claro nicht, wir müssen dafür in eine Verkaufsstelle für SIM-Karten-Aufladungen. Ein Elektronikladen in der Nähe hat den großen Claro-Aufkleber. Aber dort ist jetzt Mittagspause. Also machen wir auch erst Mittagspause und fahren dann zu dem großen Carrefour-Supermarkt, den wir auf dem Weg in die Stadt gesehen haben. Es ist eine Art Kaufhaus mit großem Non-Food-Bereich. Bei den Lebensmitteln wird große Vielfalt durch sehr große Mengen des jeweils gleichen Artikels suggeriert. Tatsächlich ist die Auswahl bescheiden im Vergleich zu Europa, aber immer noch deutlich größer, als alles was wir in Uruguay gesehen haben. Nachdem wir für einige Tage Vorräte eingekauft und verstaut haben, steuern wir wieder den Elektronikladen an. Die Kartenaufladung muss bar bezahlt werden, Kreditkarte geht nicht. Also zu einer Bank, Bargeld brauchen wir ohnehin. Zurück im Elektronikladen dauert es einige Zeit, bis wir begreifen, dass der Verkäufer keine Ahnung von den Claro-Tarifen hat. Wir gehen nochmal zu Claro nebenan. Dort kennt auch keiner die Prepaid-Tarife. Nach endlosen Minuten wird uns ein Ausdruck mit einem Ausschnitt aus den Tarifen präsentiert, mit maximal 4 GB für 30 Tage. Das ist völlig unzureichend. Nach einiger Diskussion wird uns schließlich ein Tarif mit 25 GB für 30 Tage dargelegt. Den buchen wir im Elektronikladen. Wieder dauert es, bis das erledigt ist. Eine Quittung gibt es nicht. Der erste Test auf Funktion schlägt fehl, aber nach einiger Zeit funktioniert das Internet doch. Inzwischen ist es dunkel und wir brauchen noch einen Stellplatz für die Nacht. Am Salto Grande, gegenüber der Stelle, wo wir die letzte Nacht verbracht haben, haben wir rechtzeitig bei „I Overlander“ ein paar potenzielle Stellen recherchiert. Auf der Fahrt dort hin „erleben“ wir einige Verkehrsteilnehmer, die ganz ohne Licht oder mit Warnblinkanlage statt Fahrlicht unterwegs sind. Der angesteuerte Stellplatz ist nicht erreichbar und so landen wir auf einem idyllischen Platz am Wasser bei einem kleinen Yachthafen. In der Nacht schlafen mindestens ein Dutzend Capybaras (Wasserschweine) in der Nähe unseres Womo. Am Morgen sind sie weg, aber dann zieht eine vierköpfige Gruppe im Gänsemarsch an uns vorbei. Später sehen wir sie im Schatten eines Busches liegen. Dort lassen sie sich nicht aus der Ruhe bringen.

To Argentina After two and a half weeks in Uruguay, thirteen days of which and about 1,400 km in a motorhome, we are leaving the country for the time being. We want to be back in April, in the South American autumn. On the dam of Embalse Salto Grande we cross the border to Argentina. Passport and customs clearance for both countries is in a building on the Argentinian side. Highest concentration is required here. It takes a while until we find the person in charge at Uruguayan customs, who takes the „passport“ for the vehicle issued by customs in Montevideo from us and completes the process digitally. There are no exit stamps in our passports, they have been abolished. At the Argentinian immigration office, our data is recorded digitally, there is not even an entry stamp here. All entries and exits are digitally recorded and processed, at all border crossings. We have to hope that this works everywhere. The young man who „processed“ us here speaks good English and accompanies us to the Argentinian customs. There he motivates the older customs officer, who is obviously struggling with data processing, to record the data of our camper van and driver. It takes a while until he issues us the document whose Uruguayan counterpart we had to hand in before. After about an hour, we can enter Argentina (and stay for 90 days). The first thing we have to do is run some errands. On the way to Concordia we fill up with diesel, which is cheaper here than in Uruguay. Then we get a SIM card for mobile internet. At Claro, the network provider with the best coverage in Argentina, we get the card for free. To use it, it has to be topped up. We can’t do that in Claro’s big shop, so we have to go to a shop for SIM card recharges. An electronics shop nearby has the big Claro sticker. But it’s lunch break there now. So we take a lunch break first and then drive to the big Carrefour supermarket we saw on the way into town. It is a kind of department stores‘ with a large non-food section. In the food section, great variety is suggested by very large quantities of the same item in each case. In fact, the selection is modest compared to Europe, but still much larger than anything we saw in Uruguay. After we have bought and stowed away supplies for a few days, we head for the electronics shop again. We have to pay for the card charge in cash, credit cards are not accepted. So we go to a bank, we need cash anyway. Back in the electronics shop, it takes some time before we realise that the shop assistant has no idea about the Claro rates. We go back to Claro next door. There, no one knows about the prepaid tariffs either. After endless minutes, we are presented with a printout with an extract from the tariffs, with a maximum of 4 GB for 30 days. That is completely insufficient. After some discussion, we are finally presented with a tariff with 25 GB for 30 days. We book it in the electronics shop. Again, it takes time until it is done. There is no receipt. The first test for function fails, but after some time the internet works. By now it is dark and we still need a pitch for the night. At the Salto Grande, opposite the place where we spent the last night, we researched a few potential spots at „I Overlander“ in good time. On the way there we „experience“ some road users who are driving without lights or with hazard lights instead of driving lights. The pitch we were aiming for is not accessible, so we end up on an idyllic spot by the water at a small marina. During the night, at least a dozen capybaras sleep near our camper. In the morning they are gone, but then a group of four passes us in single file. Later we see them lying in the shade of a bush. There they do not let themselves be disturbed.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . Argentinien ist ein sehr großes Land und so sind wir mehrere Tage unterwegs, bis wir die Provinz Misiones im Nordosten erreicht haben. Hier wollen wir Wasserfälle sehen. Den Anfang macht der Salto Pacá. Die letzten drei Kilometer sind eine ziemlich üble Schotter- und Erdstraße mit steilen Abschnitten. Belohnt werden wir nicht nur mit dem Wasserfall sondern auch mit einem Traum von einem einsamen Stellplatz. Ein unscheinbarer Bach stürzt hier über eine hohe senkrechte Wand in die Tiefe des Dschungels. Es ist verblüffend, welche Wirkung das relativ wenige Wasser, das wir oberhalb kaum wahrgenommen haben, als Wasserfall hat. Eine Treppe mit Stahlgeländer führt durch den Dschungel hinab in den Kessel bis vor die Aufschlagstelle des Wassers.

Argentina is a very large country and so we are on the road for several days until we reach the province of Misiones in the northeast. Here we want to see waterfalls. We start with the Salto Pacá. The last three kilometres are a pretty nasty gravel and dirt road with steep sections. We are rewarded not only with the waterfall but also with a dream of a secluded pitch. An inconspicuous stream plunges here over a high vertical wall into the depths of the jungle. It is amazing what effect the relatively little water, which we hardly noticed above, has as a waterfall. A staircase with steel railings leads down through the jungle into the cauldron to in front of the water’s point of impact.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Zufällig entdecken wir auf einer Karte einen weiterer Wasserfall, einige Kilometer vom Salto Pacá entfernt. Die anstrengende Zufahrt ist noch weiter. Über den Salto Carpes stürzt das Wasser auf breiter Front in mehreren Strömen. Ein sehr erfrischender Anblick angesichts hochsommerlicher Temperatur von etwa 30°C.

By chance we discover another waterfall on a map, a few kilometres away from Salto Pacá. The strenuous access road is even further. Over the Salto Carpes, the water falls in several streams on a broad front. A very refreshing sight in view of the high summer temperature of about 30°C.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Die argentinische Provinz Misiones war mal ein Dschungel. Wesentliche Bereiche der Reste dieses Urwalds werden im Reserva de Biósfera Yabotí geschützt. Nordöstlich von El Soberbio breitet es sich aus bis zur brasilianischen Grenze, die hier von großen Flüssen gebildet wird. An der asphaltierten Straße in den Park hinein sind an einigen Stellen Aussichts- bzw. Panoramapunkte ausgebaut. An einem davon haben wir einen besonders ruhigen Stellplatz für die Nacht. Am frühen Morgen liegt über den Flüssen im Park Nebel, der sich bald auflöst. Doch dann verschwindet die Sonne hinter den Wolken, ein Gewitter zieht auf. Nachdem es durchgezogen ist und den Dschungel getränkt hat, steigen Nebelfetzen auf. Den gewaltigen Wasserfall, den wir uns ansehen wollten, müssen wir vertagen.

In the Yabotí Biosphere Reserve The Argentinean province of Misiones was once a jungle. Substantial areas of what remains of this primeval forest are protected in the Reserva de Biósfera Yabotí. Northeast of El Soberbio, it spreads out to the Brazilian border, which is formed here by large rivers. Along the asphalted road into the park, there are viewing or panoramic points at several places. At one of them we have a particularly quiet place to camp for the night. In the early morning there is fog over the rivers in the park, which soon dissipates. But then the sun disappears behind the clouds and a thunderstorm moves in. After it has passed through and soaked the jungle, wisps of fog rise. We have to postpone the huge waterfall we wanted to see.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Wieder haben wir einen wunderbaren Stellplatz, an einem anderen Aussichtspunkt. Die Nacht ist sternenklar, am Morgen liegen dicke Nebelpakete über den Flüssen. Die Sonne lässt den frisch gewässerten Dschungel leuchten.

Again we have a wonderful pitch, at another vantage point. The night is starry, in the morning thick packs of fog lie over the rivers. The sun makes the freshly watered jungle glow.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Der eigentliche Grund, die Reserva de Biósfera Yabotí zu besuchen, ist der längste bekannte Längswasserfall der Welt, Gran Salto Moconá oder Saltos del Moconá. Das Flussbett des Rio Uruguay, der hier die Grenze zwischen Argentinien und Brasilien markiert, verläuft über drei Kilometer auf der Kante einer Schlucht. Bei Hochwasser existiert der Wasserfall nicht. Je weniger Wasser der Fluss führt, umso mehr entsteht der Eindruck vieler paralleler Fälle. Um dieses einzigartige Naturschauspiel zu sehen, muss man eine Fahrt mit einem der Schlauchboote buchen, die dafür hier eingesetzt sind. Wir bekommen eine Schwimmweste „angezogen“, dann dürfen wir mit einem weiteren Paar das Boot besteigen. Auch einige hundert Meter hinter dem Wasserfall, wo die Boote starten, ist der Fluss immer noch ein heftiges Wildwasser. Entsprechend ist die Bootsfahrt mit hoher Geschwindigkeit ein „Höllenritt“. Immer wieder krachen Wellen links, rechts und vorn gegen den Bootsrumpf und werfen es hin und her, auf und ab. Der Bootsführer ist cool. Mit einer Hand halten wir uns fest, an einem Seilknoten, am Sitz. Mit der anderen fotografieren wir. Dass dabei brauchbare Fotos entstehen, ist ganz wesentlich dem Bildstabilisator in der Kamera zu verdanken. Immer wieder wird das Boot direkt vor die Fälle gesteuert, die fast mit Händen greifbar werden. Als die Fahrt nach nur zwanzig Minuten zu Ende ist, fühlen wir uns wie nach einem sehr anstrengenden Arbeitstag.

The real reason to visit the Reserva de Biósfera Yabotí is the longest known longitudinal waterfall in the world, Gran Salto Moconá or Saltos del Moconá. The riverbed of the Rio Uruguay, which marks the border between Argentina and Brazil here, runs for three kilometres along the edge of a gorge. At high water, the waterfall does not exist. The less water the river carries, the more the impression of many parallel falls is created. To see this unique natural spectacle, you have to book a trip on one of the inflatable boats that are used for this purpose here. We get a life jacket put on, then we are allowed to board the boat with another couple. Even a few hundred metres past the waterfall where the boats start, the river is still a violent white water. Accordingly, the boat ride at high speed is a „hell ride“. Again and again waves crash left, right and in front against the hull of the boat, tossing it back and forth, up and down. The skipper is cool. We hold on with one hand, to a rope knot, to the seat. With the other we take photos. The image stabiliser in the camera is largely responsible for the usable photos. Again and again, the boat is steered directly in front of the falls, which become almost tangible with our hands. When the trip is over after only twenty minutes, we feel like after a very exhausting day at work.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Die Wasserfälle des Rio Iguazú zählen zu den drei größten der Welt, neben den Victoriafällen in Afrika und den Niagarafällen in Nordamerika. Warum sie als die schönsten gelten, ist in den folgenden Fotos zu sehen. Auf einer gesamten Breite von rund 2700 m stürzen durchschnittlich 1700 m3 Wasser in der Minute über etwa 275 einzelne Fälle. Die Grenze zwischen Argentinien und Brasilien verläuft durch den Fluss. Der Löwenanteil der Wasserfälle liegt in Argentinien und hier kommt man besonders gut an sie heran. Was wir hier sehen und erleben, ist einzigartig, wunderschön und ganz besonders sehenswert. Darum haben wir uns entschieden, verschiedene Aspekte dieser faszinierenden Wasserwelt im Dschungel in mehreren Blogbeiträgen zu präsentieren. Unterschiedliche Wanderwege eröffnen ganz verschiedene Ansichten der Fälle. Mit Ab- und Aufstiegen über Treppen gilt der Circuito Inferior als einer der anstrengenderen. Für ihn entscheiden wir uns am frühen Morgen, als es noch nicht so warm ist. Dieser bestens ausgebaute Weg führt von unten an einige der Wasserfälle heran und bietet Ausblicke auf einige der weiter entfernt liegenden sowie auf den (abfließenden) Rio Iguazú Inferior.

The Rio Iguazú Waterfalls are among the three largest in the world, along with Victoria Falls in Africa and Niagara Falls in North America. Why they are considered the most beautiful can be seen in the following images. Over a total width of about 2700 m, an average of 1700 m3 of water plunges every minute over about 275 individual falls. The border between Argentina and Brazil runs through the river. The lion’s share of the waterfalls is in Argentina and here you can get particularly close to them. What we see and experience here is unique, beautiful and especially worth seeing. That is why we have decided to present different aspects of this fascinating water world in the jungle in several blog posts. Different hiking trails open up very different views of the falls. With descents and ascents over stairs, the Circuito Inferior is considered one of the more strenuous. We choose it early in the morning, when it is not yet so warm. This well-maintained path leads to some of the waterfalls from below and offers views of some of those further away as well as to the (flowing off) Rio Iguazú Inferior.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Auf dem oberen Rundweg Circuito Superior gehen wir über Metallgitterstege über die Abbruchkanten einiger der Wasserfälle des Rio Iguazú hinweg. Dieser Weg ist eben und offenbar behindertengerecht gestaltet. Streckenweise führt er über die große Wasserfläche des (zufließenden) Rio Iguazú Superior. Sein Umkehrpunkt liegt über dem gewaltigen Salto San Martín.

On the upper Circuito Superior we walk over metal lattice walkways over the break-off edges of some of the Rio Iguazú waterfalls. This path is level and apparently handicapped accessible. In places it leads over the large expanse of water of the (inflowing) Rio Iguazú Superior. Its return point is above the mighty Salto San Martín.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Die Wasserfälle des Rio Iguazú sind Nationalpark (Parque Nacional Iguazú) und UNESCO Welterbe. Dazu gehört auch der Dschungel um die Wasserfälle herum und überall dazwischen. Mitten hindurch gehen wir, auf den vorbildlich gestalteten und bestens gepflegten Wanderwegen, über weite Strecken als Metallgitterstege. So durchqueren wir Areale, die sonst unerreichbar wären, weil sie von den Wasserläufen abgetrennt aber auch völlig undurchdringlich sind. Und uns begegnen einige exotische Tiere, u.A. Nasenbären und Schmetterlinge.

Jungle at the Rio Iguazú The waterfalls of the Rio Iguazú are a national park (Parque Nacional Iguazú) and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This also includes the jungle around the waterfalls and everywhere in between. We walk right through the middle of it, on the exemplarily designed and well-maintained hiking trails, over long stretches as metal lattice walkways. In this way, we cross areas that would otherwise be inaccessible because they are separated from the watercourses but also completely impenetrable. And we encounter some exotic animals, including coatis and butterflies.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Das Nonplusultra der Wasserfälle des Rio Iguazú ist der Garganta del Diablo. Eine kleine Schmalspurbahn fährt etwa 25 Minuten durch den Dschungel zum Beginn des Steges, der zu diesem riesigen Trichter führt. Auch er verläuft auf 1,1 km über die große Wasserfläche des zufließenden Rio Iguazú. Inseln im Fluss unterbrechen die Metallgitterstege und bieten Schatten in kleinen Dschungeln. Auf dem letzten Wegstück wird das tobende Rauschen immer lauter. Jetzt ist zu erkennen, mit welcher Macht das Wasser in den „Schlund“ zerrt. Schließlich stehen wir direkt über dem Wasserfall, in der erfrischenden Gischt. Die Schlucht ist nicht kreisrund; an ihren Wänden stürzt ein Wasserfall neben dem anderen hinab.

Devil’s Throat The ultimate of the Rio Iguazú waterfalls is the Garganta del Diablo. A small narrow-gauge railway takes about 25 minutes through the jungle to the beginning of the footbridge leading to this huge funnel. It also runs for 1.1 km over the large expanse of water of the inflowing Rio Iguazú. Islands in the river interrupt the metal grid walkways and provide shade in small jungles. On the last stretch, the raging roar becomes louder and louder. Now you can see the power with which the water is tearing into the „maw“. Finally, we stand directly above the waterfall, in the refreshing spray. The gorge is not circular; on its walls one waterfall tumbles down next to the other.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Auf dem weiten Weg vom Rio Iguazú im Nordosten zu den Anden im Westen Argentiniens haben wir im Parque Nacional Chaco Station gemacht. Er liegt nur ein paar Kilometer abseits unserer Route und bietet einen guten öffentlichen (gebührenfreien) Campingplatz. Sogar Duschen mit warmem Wasser sowie Strom sind kostenlos verfügbar, die Sanitäranlagen sind sehr sauber. Wie auf allen öffentlichen Campingplätzen, die wir bisher in Argentinien und Uruguay gesehen haben, ist unter Bäumen eine große Anzahl Grillstellen verfügbar. Mindestens am Wochenende werden die rege genutzt. In der Nacht haben wir das gesamte Areal für uns allein. Am Samstag-Vormittag treffen einige Familien und kleine Gruppen ein. Ein paar von ihnen machen die Rundwanderung, alle grillen. Der Park soll die ursprüngliche Pflanzenwelt des Chaco schützen. Der Gran Chaco ist ein Trockenwaldgebiet, das sich über Bolivien, Paraguay und etwa bis hierher in Argentinien erstreckt. U.A. sollen Wälder des Quebracho-Baums geschützt werden. Er wird sehr groß und dick, sein Holz ist sehr schwer, aber auch sehr hart. Die Bäume wurden und werden dafür gefällt und sind im Bestand bedroht.

Chaco National Park On the long way from Rio Iguazú in the northeast to the Andes in the west of Argentina, we stopped at Parque Nacional Chaco. It is only a few kilometres off our route and offers a good public (free of charge) campsite. Even showers with hot water and electricity are free, the sanitary facilities are very clean. As at all public campsites we have seen so far in Argentina and Uruguay, a large number of barbecue sites are available under trees. At least on weekends, they are used a lot. At night we have the whole area to ourselves. On Saturday morning, some families and small groups arrive. A few of them do the circular walk, all of them barbecue. The park aims to protect the original flora of the Chaco. The Gran Chaco is a dry forest area that stretches across Bolivia, Paraguay and roughly as far as here in Argentina. Among other things, forests of the quebracho tree are to be protected. It grows very large and thick, its wood is very heavy, but also very hard. The trees have been and are being felled for this purpose and their existence is threatened.

. . . Den Sendero (Wanderweg) del Rio Negro gehen auch wir. Noch vor seinem Beginn stehen zwei Flaschenbäume, mit gigantischen Dornen besetzt. Der Weg führt per Hängebrücke über den Fluss, in dem das Wasser steht, und durch einen faszinierenden Dschungel. Der ist teils bizarr und vor Allem grün. Neben wenigen Blüten bringen einzelne Jacaranda-Bäume abweichende Farben in das Grün. Die einzigen Tiere, die sich uns zeigen, sind Vögel.

We too walk the Sendero (hiking trail) del Rio Negro. Even before it begins, there are two bottle trees, covered with gigantic thorns. The path leads by suspension bridge over the river, where the water stands, and through a fascinating jungle. The jungle is partly bizarre and above all green. Apart from a few flowers, a few jacaranda trees bring divergent colour to the green. The only animals we see are birds.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Unser Weg führt uns aus der Ostseite des Parque Nacional Chaco, wo Campingplatz und Wanderwege sind, um den relativ kleinen Park herum. Auf der Westseite sehen wir ein ganz anderes Landschaftsbild: Sumpfland und Palmenhaine. Auch sie soll der Park schützen. Und dann entdecken wir nicht weit von der Straße Jabirus, eine amerikanische Storchenart.

Chaco NP, west side Our route takes us out of the eastern side of the Parque Nacional Chaco, where the campsite and hiking trails are, and around the relatively small park. On the west side we see a completely different landscape: marshland and palm groves. The park is supposed to protect them, too. And then, not far from the road, we discover jabirus, an American stork species.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Vor mehr als 6000 Jahren ist in einem etwa 4 km x 15 km großen Areal im Gebiet der Grenze zwischen den Provinzen Chaco und Santiago del Estero ein Meteoritenregen nieder gegangen. Das muss ein sehr beeindruckendes Ereignis gewesen sein (beeindruckend im Wortsinn), denn einige hundert Klumpen aus Eisenmetallen verschiedener Größe sind hier eingeschlagen. Der größte bisher gefundene wiegt über 30 Tonnen. Es ist der zweitgrößte weltweit. Die Provinz Chaco hat hier einen schönen, großen Park angelegt, den Campo del Cielo (Himmelsfeld), und darin die großen Exemplare ausgestellt. Als Dekoration sind verschiedene große Kakteen gepflanzt, die gut gedeihen. Ein riesiger öffentlicher Campingplatz mit Grillstellen und Grill-Backöfen unter Bäumen ist Teil des Parks.

Sky Field More than 6000 years ago, a meteorite shower fell in an area of about 4 km x 15 km in the area of the border between the provinces of Chaco and Santiago del Estero. This must have been a very impressive event (impressive in the literal sense of the word), because several hundred lumps of ferrous metals of various sizes have fallen here. The largest one found so far weighs over 30 tonnes. It is the second largest in the world. The province of Chaco has created a beautiful, large park here, the Campo del Cielo (Sky Field), and exhibited the large specimens there. Various large cacti have been planted as decoration and are thriving. A huge public campsite with barbecue areas and barbecue ovens under trees is part of the park.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Der ganze Park ist bevölkert von Wellensittichen, die hier nisten. Einige sind offenbar gerade mit Nestbau beschäftigt und tragen dafür grüne Zweige im Schnabel. Eine große Anzahl von ihnen sitzt in den Stahlstreben des Dachs einer großen, offenen Veranstaltungshalle und verursachen dort mit ihrem Zwitschern und Schimpfen einen Höllenlärm.

The whole park is populated by budgies that nest here. Some of them are obviously busy building nests, carrying green twigs in their beaks. A large number of them perch in the steel struts of the roof of a large, open event hall and make a hell of a racket there with their chirping and scolding.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Aus der Brett-flachen Pampa kommend fahren wir hinter Santa Lucía in der Provinz Tucumán um ein paar Kurven und finden uns auf einer rasant ansteigenden Bergstraße wieder. Damit nicht genug, führt sie auch mitten durch einen üppigen Dschungel. Die Ruta Nacional 307 verläuft hier über viele Kilometer am Bach Los Sosa entlang. Im Naturschutzgebiet Reserva Provincial Los Sosa finden wir einen Parkplatz mit Zugang zum Bach. Wir sind völlig verblüfft über diesen extremen Kontrast zu den trockenen Regionen, die wir in den vergangenen Tagen durchquert haben.

Mountain Jungle at the Los Sosa Coming out of the board-flat pampas, we drive around a few bends past Santa Lucía in the province of Tucumán and find ourselves on a rapidly ascending mountain road. As if that wasn’t enough, it also leads through the middle of a lush jungle. The Ruta Nacional 307 runs here for many kilometres along the Los Sosa stream. In the nature reserve Reserva Provincial Los Sosa we find a car park with access to the stream. We are completely amazed by this extreme contrast to the dry regions we have crossed in the past few days.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Am Ziel unserer Tagesetappe in El Mollar, auf 1850 m Höhe, gelangen wir unmittelbar zu der spektakulären „Einspeisung“ des Los Sosa: Aus dem Stausee Embalse El Mollar wird unterhalb der Staumauer Wasser offenbar direkt aus der Turbine abgelassen. Das ist eine außergewöhnliche Fontäne, die Tag und Nacht sprüht (die Fläche vor der Fontäne ist ein guter und ruhiger Stellplatz, den wir gern genutzt haben).

At the end of our day’s etappe at El Mollar, at an altitude of 1850 m, we immediately come to the spectacular „feed“ of the Los Sosa: from the reservoir Embalse El Mollar, water is apparently discharged directly from the turbine below the dam wall. This is an extraordinary fountain that sprays day and night (the area in front of the fountain is a good and quiet pitch, which we enjoyed using).

. . . . . . . . .South America Tour

In Montevideo

Am Rio de la Plata

Punta del Este

Schären an Uruguays Küste

Flysch bei La Paloma

San Antonio Strand

Isla Negra

Quebrada de los Cuervos

Campo

Wildtiere im Campo

Am Salto Grande

Nach Argentinien

Salto Pacá

Salto Carpes

Im Yabotí Biosphärenreservat

Saltos del Moconá

Cataratas del Iguazú

Iguazú, Circuito Superior

Dschungel am Rio Iguazú

Iguazú Teufelsschlund

Chaco-Nationalpark

Chaco-NP, Westseite

Himmelsfeld

Berg-Dschungel am Los Sosa